Neuropsychology in Chile

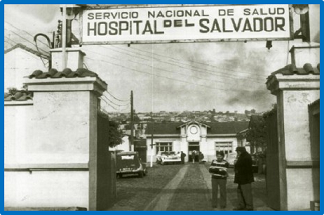

My valuable experience working at the Neurology Department of Hospital del Salvador in Santiago de Chile

Picture by Carlos Muñoz-Neira

Picture by Carlos Muñoz-NeiraNeuropsychology in Chile

In this post I would like to let you know in general terms what neuropsychology is (for those who are not that familiar with the subject) and how this field is related to dementia. In addition, I have decided to also present here the work that I managed to carry out in Chile when I worked in the Neurology Department of Hospital del Salvador between 2010 and 2016 approximately, hence the photo enclosed to this publication. I recommend taking a look into the chapter on neuropsychological assessment of the Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementias published by the Society for Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery (SONEPSYN) (1) for a more complete review on this matter. Parts of such a chapter are included in this post. If any of you have also done research in neuropsychology in Chile and you would like to broadcast your findings here, please, do not hesitate to contact me and perhaps I can publish what you think is OK in this website.

Neuropsychology, clinical neuropsychology and neuropsychological evaluation

Neuropsychology can be defined as a body of knowledge devoted to exploring the possible existing relationships there are between the brain, cognitive activity, emotions and behaviour. This purpose is addressed from a perspective based on neurosciences. Pursuing this line of reasoning, clinical neuropsychology is aimed at understanding how those domains vary in healthy people or people with brain disorders. Thus, clinical neuropsychology provides procedures useful to assess and treat the neuropsychological/neuropsychiatric consequences of brain disorders (2). Likewise, the neuropsychological assessment is a tool that sets the methods necessary to collect information on clinical aspects of the patient in reference making use of use of cognitive tests conducted on them and scales administered to both the patient in reference and their reliable informant. Neuropsychological assessment yields a systematic description then about the potential consequences of a brain disorder in terms of the global cognitive state of a patient, their attention, language, episodic memory, visuospatial abilities, executive functions, neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional capacity in activities of daily living (3).

Objectives and importance of neuropsychological assessment in dementia

Dementia can be understood as a syndrome of cerebral aetiology (either neurodegenerative, neurovascular or other) that importantly affects cognition, behaviour and functional capacity in activities of daily living (4). Neuropsychological assessment is a useful procedure to examining such domains making use of various cognitive tests and scales. Both neuropsychological testing and collection of clinical information through questionnaires are relevant because they can contribute to the identification of recent neuropsychological/behavioural changes and facilitate the follow-up of the course of the disease of a patient. In this way, neuropsychological assessments as a clinical procedure can help health care professionals keep a record of the patient’s symptomatology to document or rule out the presence of a brain disorder, differentiate genuine cognitive decline from subjective cognitive complaints and cognitive problems compatible with normal ageing, identify the possible presence of dementia and/or detect its prodromal phase. Neuropsychological assessment can also provide guidance on the possible location of brain dysfunctions in the absence of neuroimaging and contribute to the differential diagnosis of different forms of dementia (5).

Neuropsychological tests used in Chile

My work experience at the Neurology Department of Hospital del Salvador was very enriching. I managed to combine clinical and research work being part of the Cognitive Neurology and Dementias Unit (UNCD). I actively participated in the validation of several neuropsychological tools there, which ended up being published in different scientific journals. Fortunately, I was the first author or a co-author of some of those publications. I will leave you here a photo that was taken at the entrance of the Neurology Service of Hospital del Salvador just before I moved to England.

Cognitive screening instruments administered to patients

The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination - Revised (ACE-R) (6) is a practical cognitive screening tool that explores 5 cognitive domains including orientation and attention, memory, language, fluency, and visuospatial skills. The ACE-R was designed to tackle the disadvantages of the Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE) (7), although it is possible to obtain scores for both tools only administering the ACE-R. In addition, the ACE-R has the advantage of providing a statistical value to differentiate different types dementia, such as those with an amnesic profile from the ones exhibiting a frontal profile. The Chilean validation we carried out indicated good psychometric properties for the test, which we finally called ACE-R-Ch (8). An interesting alternative to the ACE-R-Ch might be the cognitive screening Test Your Memory (TYM) (9), which is available to be administered in Spanish speaking populations (Test Your Memory - Spanish Version -TYM-S-), given its validation conducted across a Chilean cohort of patients with cognitive decline and cognitively healthy older adults (10). The TYM is a cognitive screening that has the particularity of being self-administered, therefore its administration is characterized by its simplicity. Like the ACE-R-Ch, its validation presented excellent psychometric properties. A useful brief battery to assess executive dysfunction is the ‘Instituto de Neurología Cognitiva (INECO) Frontal Screening’ (IFS) (11). This tool includes motor sequence tasks (Luria test), inhibitory control, and resistance to interference, among other frontal tasks. The IFS has also a Chilean validation that we decided to call IFS-Ch. Fortunately, this test showed appropriate psychometric properties too (12).

Informant-based scales for the assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional capacity in activities of daily living

Complementary assessments based on patients’ reliable informants concern the administration of scales or questionnaires useful to document the presence of neuropsychiatric/behavioral symptoms and/or functional impairment that dementia patients have been showing lately. These scales or questionnaires should be always filled in by key informants such as the dementia patient’s spouse or their close relative. In terms of neuropsychiatric symptoms, we recently validated the Neuropsychiatric Inventory - Questionnaire (NPI-Q) (13) in Chile (14). This tool contributes to identifying symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, depression and apathy, among others. Concerning the assessment of functional capacity, the Technology - Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire (T-ADLQ) (15) is a scale we also validated in Chile to count on a thorough method to evaluate functional impairment in basic, instrumental and advanced activities of daily life. This tool was developed making use of the original Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire (16). I would like to mention here that this validation study was the final product of my undergraduate thesis! (15).

Why is neuropsychological evaluation so useful in the clinical practice of dementia?

The selection of the pertinent neuropsychological tool to assess cognitive or behavioural changes depends on the time available, the experience of the examiner, the psychometric properties of the test or scale in reference and the context in which the tool will be used. The need to employ neuropsychological assessments in cases of possible cognitive decline has become increasingly relevant given that the diagnostic criteria for dementia require a formal evaluation and an “objective” documentation of cognitive, behavioural and/or functional changes. Broadly speaking and only to draw didactic examples, a neuropsychological assessment can be helpful in describing a traditional amnesic disorder that could result from the involvement of medial temporal brain areas, and therefore characteristic of an amnestic mild cognitive impairment or an early Alzheimer’s disease. In contrast, a dysexecutive syndrome observed through a neuropsychological assessment might suggest fronto-subcortical dysfunctions due to vascular cognitive impairment or frontotemporal dementia in case the latter situation is accompanied by profound personality changes and severe impairment of social cognition. Likewise, neuropsychological assessments can aid the characterization of a neurocognitive impairment profile secondary to a particular type of dementia. Another example can emerge from those situations where cognitive changes associated with anxiety or depressive symptoms must be distinguished from an actual insidious dementia onset. It is expected that the results of different neuropsychological tools could facilitate the understanding and differential diagnosis of different clinical pictures (1).

References

- Flores P, Munoz-Neira C. Evaluación neuropsicológica de las demencias. In: Nervi A, Behrens MI, editors. Guías clínicas de diagnóstico y tratamiento de las demencias. Chile: Ediciones de la Sociedad de Neurología, Psiquiatría y Neurocirugía de Chile; 2017. p. 173-80.

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Bigler ED, Tranel D. Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

- Hodges JR. Cognitive assessment for clinicians. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2018.

- Munoz-Neira C, Slachevsky A, Lopez OL. Neuropsychiatric Characteristics of Alzheimer’s Disease and the Behavioral Variant of Frontotemporal Dementia. JSM Alzheimer’s Dis Related Dementia. 2016;3(1):1-9.

- Labos E, Pérez C, Prenafeta ML, Slachevsky A. La evaluación en neuropsicología. In: Labos E, Slachevsky A, Fuentes P, Manes F, editors. Tratado de Neuropsicología Clínica: Bases conceptuales y técnicas de evaluación. 1era. Edición ed. Buenos Aires: Librería Akadia Editorial; 2014. p. 69-80.

- Mioshi E, Dawson K, Mitchell J, Arnold R, Hodges JR. The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R): a brief cognitive test battery for dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(11):1078-85.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-98.

- Munoz-Neira C, Henriquez Ch F, Ihnen JJ, Sanchez CM, Flores MP, Slachevsky Ch A. [Psychometric properties and diagnostic usefulness of the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised in a Chilean elderly sample]. Rev Med Chil. 2012;140(8):1006-13.

- Brown J, Pengas G, Dawson K, Brown LA, Clatworthy P. Self administered cognitive screening test (TYM) for detection of Alzheimer’s disease: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2009;338:b2030.

- Munoz-Neira C, Henriquez Chaparro F, Delgado C, Brown J, Slachevsky A. Test Your Memory-Spanish version (TYM-S): a validation study of a self-administered cognitive screening test. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(7):730-40.

- Torralva T, Roca M, Gleichgerrcht E, Lopez P, Manes F. INECO Frontal Screening (IFS): a brief, sensitive, and specific tool to assess executive functions in dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15(5):777-86.

- Ihnen J, Antivilo A, Muñoz-Neira C, Slachevsky A. Chilean version of the INECO Frontal Screening (IFS-Ch): Psychometric properties and diagnostic accuracy. Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 2013;7(1):40-7.

- Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, Smith V, MacMillan A, Shelley T, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233-9.

- Musa G, Henriquez F, Munoz-Neira C, Delgado C, Lillo P, Slachevsky A. Utility of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) in the assessment of a sample of patients with Alzheimer’s disease in Chile. Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 2017;11(2):129-36.

- Munoz-Neira C, Lopez OL, Riveros R, Nunez-Huasaf J, Flores P, Slachevsky A. The technology - activities of daily living questionnaire: a version with a technology-related subscale. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2012;33(6):361-71.

- Johnson N, Barion A, Rademaker A, Rehkemper G, Weintraub S. The activities of daily living questionnaire - A validation study in patients with dementia. Alz Dis Assoc Dis. 2004;18(4):223-30.